Don’t underestimate it, the North American Monarch butterfly is tough and powerful. It’s capable of herculean flights of 80 miles a day or more.

Don’t underestimate it, the North American Monarch butterfly is tough and powerful. It’s capable of herculean flights of 80 miles a day or more.

The Monarch, mariposa monarca (Danaus plexippus) has been on the scene in North America longer than mankind. One sees them now just as they have been for countless ages, drifting across open grassy places, investigating every flowering plant. But have you seen billions at one time? In the State of Michoacán, Mexico, you can find all of the Monarchs that spent their summer in the United States and Canada, east of the Rockies and west of the Alleghenies, in their winter haven.

The Monarchs

Some of these fragile butterflies come from as far away as the Eastern Provinces of Canada; others from the upper reaches of Minnesota. Many have traveled 4,000 or more miles to Michoacán!

Their migrations are seemingly as eternal as the movement of the earth around the sun: when the sun sheds less light, and chill puts its fingers out, the Monarch leaves the nectar-giving plants of the open fields, responding to a music they alone can hear.

(The song must be plaintive, for they know the killing cold season is upon them.) They fly singly, only during the day, at about 12 miles an hour at varying altitudes, and feed at night.

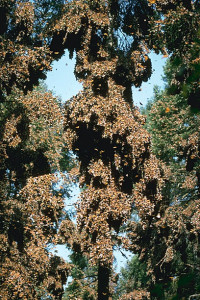

They fly into Michoacán’s eastern edge of the Sierra Madre Occidental mountain range in mid-December. By January the fir trees, Oyamel in Spanish, (Abies Religiousa) are filled with them. The temperature hovers around the freezing point. In January, were you to see them then, they would appear to be little more than a pale parasitic growth clinging to the trees in a semi-torpid state. Their wings are closed tight! But, as the days begin to lengthen again—sometimes in mid February—they move down the slopes to warmer areas, stirring and swirling, their brilliant wings filling the skies.

They fly into Michoacán’s eastern edge of the Sierra Madre Occidental mountain range in mid-December. By January the fir trees, Oyamel in Spanish, (Abies Religiousa) are filled with them. The temperature hovers around the freezing point. In January, were you to see them then, they would appear to be little more than a pale parasitic growth clinging to the trees in a semi-torpid state. Their wings are closed tight! But, as the days begin to lengthen again—sometimes in mid February—they move down the slopes to warmer areas, stirring and swirling, their brilliant wings filling the skies.

«The floor of the forest is partly covered with Monarchs; there are places where they are piled one on top of the other to a depth of 20 centimeters,» noted Dr. Fred A. Urquhart to the «National Geographic».

Only when spring comes, when the days lengthen, and their departure is imminent, will the mating process occur. This generation of females will lay their eggs on the undersides of milkweed plants as they fly north. The Monarch produces as many as four generations a year, each one of which ventures a little further north. It is the last of these that migrates back to Michoacán before the oncoming of winter.

The Sanctuaries and the Government

There are sanctuaries for the butteflies at; Ocampo, Sierra El Campanario; Contepec, El Cerro Altamirano; Angangueo, Sierra Chincua; and Zitácuaro, Chivati-Huacal and El Cerro Pelon.

It is estimated that there are about 20 million insects at each of these sites, and there are other inaccessible areas in the Rosario Reserve.

Every creature is hostage to its habitat. (We should not forget this.) Not considering the Monarch’s rights, local Tarascan Indians grub out a living as best they can, growing maize and wheat, and cutting timber. The trees that are cut down reduce the Monarch’s habitat. The butterflies need these trees to protect them from the rain, sleet and snow, and also to give them some protection from bird predators. (It is an interesting fact, while bitter tasting, even poisonous, and avoided by birds in the north, the Monarch is palatable in its wintering ground, hence a tasty morsel for any passing bird.)

Every creature is hostage to its habitat. (We should not forget this.) Not considering the Monarch’s rights, local Tarascan Indians grub out a living as best they can, growing maize and wheat, and cutting timber. The trees that are cut down reduce the Monarch’s habitat. The butterflies need these trees to protect them from the rain, sleet and snow, and also to give them some protection from bird predators. (It is an interesting fact, while bitter tasting, even poisonous, and avoided by birds in the north, the Monarch is palatable in its wintering ground, hence a tasty morsel for any passing bird.)

Some twenty years ago, upon the recommendation of the Michoacán Forestry Commission, laws were enacted to prohibit timbering in the areas where the Monarch makes its winter home. Anyone who has seen «The Treasure of the Sierra Madre» will appreciate how well laws are respected in such remote areas.

However there are a few bright notes: lately the Federal government has been enforcing the law, and has confiscated and destroyed some illegal lumber mills; and, in 1990, the irrepressible Professor Urquhart reported in the «National Geographic» that in 1989 there was a noticeable increase in the Monarch population in their winter havens.

How Their Haven Was Discovered

It was a known fact a century or more ago that some butterflies, the magnificent Monarch among them, migrate before the bitter northern cold could put an end to their lives. Scientist knew this because when spring came, they did not see them as caterpillars, but as full-grown orange, white, and black insect elves fluttering in fields and gardens, and naturalists and scientists wondered the how and where they wintered?

Most of the insect kingdom can lay eggs, (almost microscopic in size) that will withstand the rigors of Arctic fronts: when warm weather comes, the eggs hatch for a new generation. The Monarch, blessed with wings, flies to warmer climes.

And so, when the intimation of cold weather came, the lovely Monarchs disappeared. Most accepted this as the normal occurrence of things: a small group of scientists asked, «Where?» No one knew, but obviously to a warmer climate. The answer to, «Why» was in their desire to survive. «How?» Well, they had wings—beautiful, startlingly colored wings—that enabled them to flee their destruction.

Well, then, where? But scientists could only speculate: Florida?, Texas?, California? The

problem was the only known concentrations of the Monarchs in the winter were in California (principally around Pacific Grove, and none could imagine a monarch going from, say, Toronto, across the Rockies, and living to tell the tale). So, perhaps Florida?

No, naturalists in Florida reported their Monarchs had left too. (These later were found to remove themselves to the Yucatan peninsula of México—quite a feat!)

In Texas it was reported their Monarchs departed also. Southwards, of course. But where else was there but México? How could such a beautiful, spectacular, butterfly just disappear?

In Texas it was reported their Monarchs departed also. Southwards, of course. But where else was there but México? How could such a beautiful, spectacular, butterfly just disappear?

I suppose any problem which seems to have a solution that hasn’t been found, consequently attracts minds. The problem of the wintering ground of the Monarch butterfly attracted some good ones.

So let’s listen in:

From an article in the July 1937 «National Geographic Magazine» by C.B. Williams.

We look forward to being able one day to trace a migration of butterflies from its source to its goal. One method would be to build up a network of observers over a large area and to correlate all their records. Another appears to be more and more possible every year, would be to follow the swarm with an auto gyro.

[An auto gyro is an aircraft with a forward propeller and a free-wheeling heliocentric blade (like our modern helicopter, but without any power of its own), an airplane that seemed of great promise in those days, because of its low speed characteristics. Some of you may remember them; an aeronautical idea that didn’t work out.]

In the «National Geographic» of April 1963, Dr. Paul Zahl wrote,

For many years lepidopterists have marked the Monarch, hoping to discover their wintering place, but with little success. Many methods have been tried, including marking Monarchs with gummed labels, but with indifferent results.

And Professor Fred Urquhart came upon the scene. He had been studying the Monarch when Paul Zahl had his article published in the «National Geographic». Urquhart was a Canadian; the people who, along with some Minnesotans, were most interested in where the hell did the Monarchs go?

The key was in being able to tag such fragile creatures as butterflies in such a way that it would be non-destructive to its normal operations; have an easily returnable address, so they could keep records of where the Monarchs were found; and wouldn’t keep falling off!

Professor Urquhart finally discovered a way to attach a tag to the Monarch that wouldn’t incapacitate it and wouldn’t come off, either. And it did work! He, and his wife Norah, put ads in various papers calling for volunteers to tag Monarchs. There were twelve initial responses, and that was how the «Insect Immigration Association» got started. Over a number of years it became obvious that all of the Monarchs were migrating past Texas and into México.

Norah Urquhart ran an ad in several Mexican newspapers, «Could you help us find where the Monarchs have gone?»

One person, Ken Brugger, replied from Mexico City. Ken, was to find the secret of the wintering place.

«See if you can find a place where there are a congregation of Monarchs,» the Urquharts said.

«How do I go about doing that?»

«We don’t know, but look!»

He did. At first with his van and his dog; later adding a lovely Mexican wife. They prowled the back roads for signs of the Monarch. And, between Toluca and Morelia Brugger saw many Monarch butterflies which, instead of migrating, were just fluttering about aimlessly.

He did. At first with his van and his dog; later adding a lovely Mexican wife. They prowled the back roads for signs of the Monarch. And, between Toluca and Morelia Brugger saw many Monarch butterflies which, instead of migrating, were just fluttering about aimlessly.

He called the Urquharts. «I think I’ve got something!»

Ken was close to the town of Zitàcuaro, where he went to place his telephone call.

«You’re sure they weren’t going in any particular direction?» Fred Urquhart asked.

«I did notice some of them seemed to be drifting off to the North east. But some of them seemed to be going straight North.»

«Is there a town up there?» Fred asked.

«A little town called Angangueo is right up the road.»

«And you think that’s where the Monarchs were going?»

«I’m not sure, but I’ll check it out.» And he did. There, Ken found a couple of woodcutters; «Si,» they knew a place where there were many mariposas monarcas in the trees. But it was a long way from town. After climbing and descending what seemed like a hundred miles, the woodcutters led Brugger and his new bride into a grove of sheltered fir trees.

It was as if someone had opened King Tutankhamen’s Tomb—there were numberless butterflies covering every branch of every fir tree. Because, as Brugger learned later, it was mid-day, and their wings shivered and wafted in the wind! No sight could be this beautiful!

Papelandia Publishing

Expert Mexico Guide Books

by William J. Conaway

Go to: MEXICO WALKING TOURS